4 Reasons Why Every Christian Needs a Deeply Historical Faith

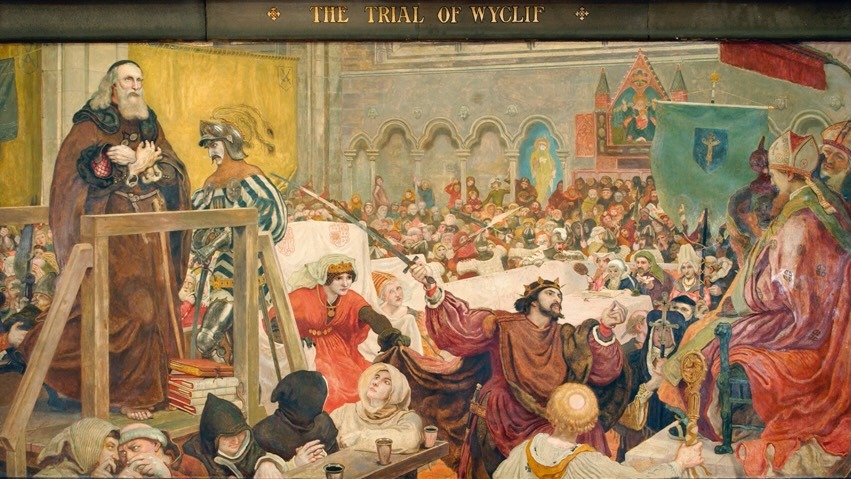

Photo Credit: “The Trial of Wycliffe A.D. 1377” by Ford Madox Brown, a mural at Manchester Town Hall; from Wikimedia Commons. To learn more about John WyCliffe., click here.

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links, meaning Beautiful Christian Life LLC may get a commission if you decide to make a purchase through its links, at no cost to you.

“Read the book before you watch the movie—it’s way better.” If you’re a novel-lover like me, you’ve probably said this before. Perhaps you’ve read Jane Austen’s books multiple times and can tell me the reasons why you hate or love certain renditions over others. Maybe you fell in love with Tolkien’s The Hobbit when you first read it, but you were horrified by how much was changed in the film.

Films are limited—oftentimes they only have 1-2 hours to portray a story that consists of many reading hours. Inner dialogue isn’t well captured, or perhaps not captured at all. Emotions must be shown by strong acting. And beloved scenes must be shortened to fit in the other necessary pieces of the plot. The journey we went on with the author and their story becomes abridged and retold.

Something similar has happened with our theology, I believe. Rich theology with its complex history has been abridged to memes, social media captions, and slogans. What was once discussed and believed from thorough exegesis and study can be summed up in pithy sentences on graphics. What took some people years of study, inquiry, and many books from a variety of libraries to understand, others today can learn in thirty minutes listening to a podcast or two minutes scanning an article. While there are good things to be taken from these, I wonder if we’ve forsaken other important things along the way. Here are four reasons why every Christian needs a deeply historical faith:

1. Many Christians aren’t connected with important historical aspects of their faith.

Perhaps the historical aspect of our faith is missing from the stories of many believers. They found Jesus on their own, and they learned about him without tradition or history coloring their glasses. It sounds so mature to say, “I follow Jesus, not [insert theologian name here].” Or, “I’m a Bible-believing Christian, not a follower of religion.” Or, “I don’t ascribe to any denomination or tradition—I ascribe to the Bible.” As simple and profound as this sounds, what if it’s not really true or helpful? What if this isn’t meant to be the ordinary way? Theologian and statesman Abraham Kuyper wrote,

No theologian following the direction of his own compass would ever have found by himself what he now confesses and defends on the ground of Holy Scripture. By far the largest part of his results is adopted by him from theological tradition, and even the proofs he cites from Scripture, at least as a rule, have not been discovered by himself, but have been suggested to him by his predecessors.[1]

Claiming that tradition has no effect on us is perhaps naïve if not dishonest—whether intentional or not.

2. Isolating ourselves from church history is unwise.

We all have backgrounds and lenses through which we read the Bible. Nobody can approach the Bible with a completely blank slate. We are part of a deeply historical faith that spans from our parents all the way back to Adam and Eve.

Isolating ourselves from church history is unwise. There’s a reason we have thorough historical creeds and confessions—they are the result of important debates, conflicts, and opposition to heresies in order to defend the essential doctrines of our faith. These biblical topics weren’t simply deliberated and discussed over steaming drinks in a coffee shop; they were debated while cannons fired in the background. “In early modernity, theology was no ivory tower endeavor—theology often wrote checks that were cashed in blood.”[2]

There’s a reason why Christians battled so fiercely for these doctrines. There’s a reason why they belabored every word in these creeds and confessions. They are important. These doctrines are essential to the gospel. When we change the basic truths about the Trinity, the atonement, the life and work of Christ, or justification, we divert to another gospel. The church has fought these same theological battles over and over again—what a treasure it is to be able to turn back in church history and see what has been confirmed and affirmed in the past and how it is founded in Scripture.

3. A critical part of maturing as believers is growing in our knowledge of what God’s word says.

Having a foundation in church history gives us the ability to re-evaluate what we believe and compare it to Scripture. Without church history, we only have present-day Bible teachers and movements with which to compare.[3] As Michael Horton writes,

It is important to recognize that we never come to the Bible as the first Christians, but always as those who have been inducted into a certain set of expectations about what we will find in Scripture. I did not find the doctrine of the Trinity all by myself. It is part of the rich inheritance in the communion of the saints from the past and the present. So the best way forward is to respect and evaluate our traditions, not to idolize or ignore them.[4]

A critical part of maturing as believers is growing in our knowledge of what God’s word says. He has given us a book with thousands of words in it written by the Holy Spirit working through men of his choosing. As we follow our Lord, shouldn’t we desire to learn more about him and how he has called us to live? As we mature, shouldn’t we desire to understand what he meant in his word and develop our theology from it?

4. Theology should be learned in community—not just local, and not just present.

As we touched on in the beginning, there’s a reason the books are always better than the movies based upon them—they are rounder and more vibrant. In a similar way, looking to our past in church history and its creeds and confessions is so much richer than a meme. This doesn’t mean each of us should quit our jobs and begin seminary to study history, or that we need to buy books we can hardly carry. We can take baby steps in understanding church history. We can ease our way into knowing the confessions and creeds. You don’t need to learn to recite each catechism by the end of the week—simply begin studying and seeking to understand them.

Theology should be learned in community—not just local, and not just present—but in the community of all believers past as well. We aren’t individual people running a race to eternal life; we’re a singular body seeking to carry one another to the finish line by the sustaining grace of God. Though some believers are already worshipping in glory, they have left pieces behind to help keep us on the right trail.

Resources for Further Study:

- Westminster Shorter Catechism

- ESV Bible with Creeds and Confessions

- A Survey of Church History, Parts 1-6 by W. Robert Godfrey (teaching series through Ligonier Ministries)

- The Theology of the Westminster Standards by J. V. Fesko

- The Truths We Confess by R. C. Sproul

This article is adapted from “The Importance of a Historical Faith” at laradentremont.com and was originally published at Beautiful Christian Life at May 5, 2020.

Related Articles:

- 4 Reasons Why the Pilgrims Came to America

- How to Discern Biblical Truth

- Christian Basics: What Are the Five “Alones” and Why Do You Need to Know Them?

- 10 Facts You Need to Know about the Reformation (Rumors and Legends Dispelled)

Recommended:

The Theology of the Westminster Standards: Historical Context and Theological Insights by J. V. Fesko

Notes:

[1] Abraham Kuyper, Principles of Sacred Theology, trans. J. Vriend; (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 1980), 574-75.

[2] J. V. Fesko, The Theology of the Westminster Standards (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2014), 48.

[3] Michael Horton, Ordinary: Sustainable Faith in a Radical, Restless World (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2014), 72.

[4] Horton, Ordinary, 72.